Suicide prevention groups should include antidepressants as a suicide risk factor, as research confirms the link to suicidal thoughts and actions in children.

Since 2004, the FDA has required a black box label on antidepressants to warn of the increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children and teenagers taking the drugs. The warning was expanded in 2007 to include young adults ages 18 through 24. The FDA website clearly lists “suicidal thinking” as one of the “serious risks” of antidepressants.

Yet antidepressant use is still not listed as a suicide risk factor on the suicide prevention websites of key government health agencies, including the National Institute of Mental Health, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Suicide Prevention Resource Center and its Suicide Prevention Lifeline, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – websites to which consumers are directed for suicide prevention information.

Likewise, “The U.S. Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Implement the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention” does not include expanding public awareness that antidepressants increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in young people.

The FDA’s initial black box warning in 2004 came after drug trials found that children taking antidepressants were almost twice as likely to have suicidal thoughts or to attempt suicide as children receiving placebos. Psychiatrists against that decision have argued that fewer youth taking antidepressants would lead to more of them committing suicide.

However, further research has re-confirmed the validity of the black box warning for children. Researchers led by professor of psychology Glen I. Spielmans, Ph.D., analyzed data from antidepressant clinical trials and published the results in Frontiers in Psychiatry in 2020. Their conclusion: “Recent data suggest that increasing antidepressant prescriptions are related to more youth suicide attempts and more completed suicides among American children and adolescents.”

In defense of the black box warning, the researchers stated: “Based on the sum of this evidence, regulatory warnings regarding antidepressant-linked suicidality are clearly warranted.”

“When a clear body of evidence points to increased treatment-linked risk, patients and health care providers should be made aware of these risks,” they added.

“More recent data suggest that increasing antidepressant prescriptions are related to more youth suicide attempts and more completed suicides among American Children and adolescents.”

– Glen I. Spielmans, PhD, professor of psychology

Another study from Denmark in 2016 re-confirmed earlier findings that children taking antidepressants are at twice the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions. Researchers at the Nordic Cochrane Centre in Copenhagen analyzed data from 70 antidepressant clinical trials and concluded that the drugs double the risk of suicide in children and teens. One of the researchers, physician Peter Gotzsche, concluded that antidepressants don’t even work for children.

The urgency of making this increased risk of suicide more widely known is underscored by the rapid increase in antidepressant prescriptions written for American children and young adults over the past 15 years. In 2006, some 3.3 million children under the age of 25 were on antidepressants. By 2020, the number had grown to more than 5.6 million, an increase of more than 70%. Shockingly, more than 41,000 of those children were age 5 or younger, including 3,200 infants under the age of 1.

Rising right along with the number of children on antidepressants were the youth suicides in this country. In 2006, a total of 4,408 children under the age of 25 took their own lives, with 219 of these tragic deaths in children age 14 or younger. By 2019, the number had increased by 47% to 6,500 suicides, with 546 committed by children age 14 or younger, a nearly 150% increase.

It is highly unnatural for a child to commit suicide. While many other risk factors can contribute to children’s depressed feeling and urge to end their lives, including family problems, traumatic life events, bullying, and exposure to suicide by others, antidepressants are still not included in the typical list of risk factors.

Donna Ruch, Ph.D., a researcher at Nationwide Children’s Hospital Center for Suicide Prevention and Research in Columbus, Ohio, and her colleagues examined the circumstances behind 134 suicide deaths of children ages 5 to 11 over the five-year period through 2017. Most of the children were between 10 and 11 years old. The analysis found that a third of the children had a mental health “diagnosis,” with ADHD and mood disorders such as depression the most common diagnoses.

Notably, 78% were receiving mental health treatment before their deaths, and 24% had a prior psychiatric hospitalization. As psychiatric drugs are the primary mode of psychiatric treatment, how many of the children in this study diagnosed with depression and receiving mental health treatment were taking antidepressants or were in withdrawal from them at the time they committed suicide?

It is not known how antidepressants work. What we do know is that the drugs disrupt the body’s normal biochemistry in ways that are not fully understood.

A team of researchers led by Paul W. Andrews, Ph.D., an associate professor of evolutionary psychology at McMaster University, analyzed previous studies to determine the overall physical impact on the human body of antidepressants that target serotonin. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that, in the course of the evolutionary adaptations of the human body, has come to regulate emotion, development, nerve cells, the clotting process, attention, electrolyte balance, and reproduction.

The researchers’ conclusion, published in 2012 in Frontiers in Psychology, was straightforward: “Our review supports the conclusion that antidepressants generally do more harm than good by disrupting a number of adaptive processes regulated by serotonin.”

Psychiatrist Peter Breggin, M.D., describes antidepressants as neurotoxic because they harm and disrupt the functions of the brain, causing abnormal thinking and behaviors that include anxiety, irritability, hostility, aggressiveness, loss of judgment, impulsivity, and mania, which can lead to violence and suicide.

The young are particularly vulnerable to these adverse effects, according to Breggin: “The harmful mental and behavioral effects of antidepressants are especially prevalent and severe in children and youth.”

Even worse for many are the physical and emotional withdrawal symptoms that can be experienced when discontinuing antidepressants, especially after long-term use. Withdrawal symptoms can include flu-like symptoms, insomnia, nausea, imbalance, hyperarousal, and the sensory disturbances often referred to as electric shocks or “brain zaps.”

Antidepressants can also take away the joy in life. “In the long run, antidepressants, like almost all psychiatric drugs, lead to apathy, indifference, and lack of caring,” writes Breggin. “Emotional life is dulled and relationships lack empathy and love.”

Parents have a right to know these risks of antidepressants, and especially the increased risk of suicidal thoughts and actions in children, prior to giving any consent. Children are among our most vulnerable members of society, and parents cannot make fully informed decisions about starting or stopping antidepressants for their children without this vital information.

As Professor Andrews put it: “We conclude that altered informed consent practices and greater caution in the prescription of antidepressants are warranted.”

In combating the growing number of child suicides, the Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) continues to push for more widespread public awareness of the increased the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior for young people taking antidepressants.

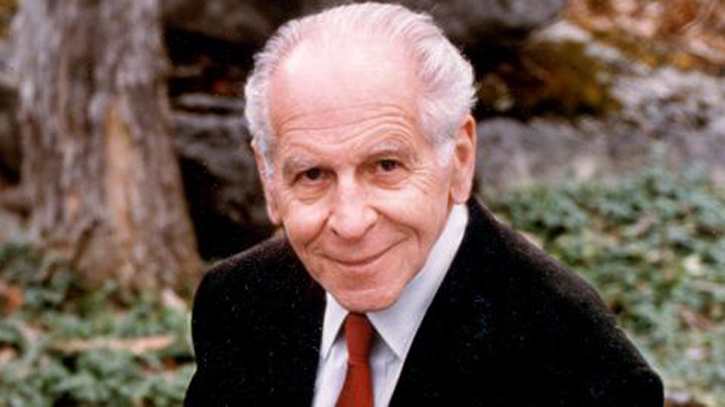

CCHR was co-founded by the late psychiatrist and humanitarian Thomas Szasz, M.D., recognized by many academics as modern psychiatry’s most authoritative critic. Concerning the psychiatric practice of “diagnosing” and drugging children, Dr. Szasz wrote: “Labeling a child as mentally ill is stigmatizing, not diagnosis. Giving a child a psychiatric drug is poisoning and punishment, not treatment.”

CCHR has long recommended that individuals experiencing depression should ask their physician for a complete physical examination with lab tests to discover any underlying physical conditions that could be causing the mental symptoms that would otherwise be misdiagnosed as mental disorders. Many prescription drugs, including antidepressants, are known causes of depression, and a physician should re-evaluate whether to continue prescribing the drugs.

WARNING: Anyone wishing to discontinue or change the dose of an antidepressant is cautioned to do so only under the supervision of a physician because of potentially dangerous withdrawal symptoms.